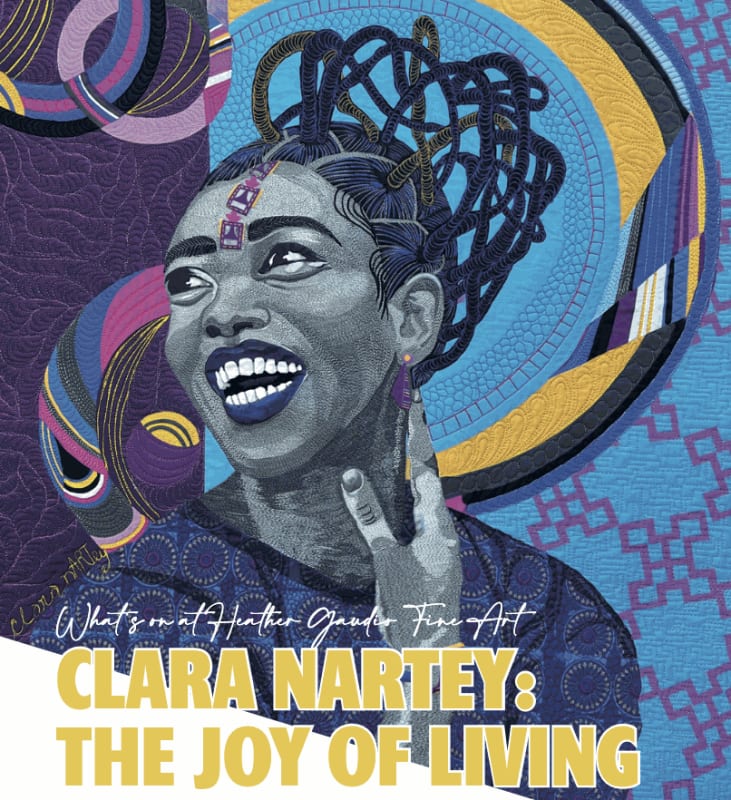

Color and joy have descended in downtown New Canaan at Heather Gaudio Fine Art PROJECTS. The show features richly saturated portraits and figurative works created with thread and embroidery by Clara Nartey. For the artist, these works are as much emotive expressions of elation as they are a representation of a very personal journey. Nartey’s practice mixes an aesthetic history that explores culture and identity through a traditional medium.

Born in Ghana, Nartey moved to New York, where

she earned her MBA, then moved to Massachusetts,

before settling permanently in Connecticut. As was

the tradition in her family, she’d learned to stitch and

embroider from her mother, but for Nartey, the sewing

machine represented a respite from the world of

finance. Never would she have envisioned becoming

a full-time artist with said machine – it took the

economic downturn of 2008 to present her with new

opportunities. With a change in career, Nartey was

able to dedicate more time to artistic investigations,

developing collaged explorations of color and abstract

patterns that reflected her culture.

As she perfected her embroidery techniques and

began to expand her lexicon into quilted patchwork

designs, the self-taught artist had an experience which

was to have a lasting personal and artistic impact.

While waiting for an interview at her daughter’s

private school, Nartey encountered an African

American woman proudly wearing her hair naturally.

Centuries of Eurocentric norms have dictated the

aesthetic standards for women in society, particularly

in a professional setting. African women have had to

conform to meet these norms by treating their naturally

curly hair with chemicals and straighteners. Nartey

realized that years of self-negation and wanting to fit

in had denied her from embracing her authenticity. “It

took a lot of courage, and it was a very personal journey,”

the artist states, for her to allow her hair to regain its

natural form. This pivotal moment also saw a shift in

her artwork, which turned from abstracted patterned

shapes to depicting the figure. Nartey’s visual language

shifted to disrupt the societal understanding of beauty

to where Black women could see themselves

and imagine new possibilities.

Although stitchwork has traditionally been associated

with domesticity and has been dismissed as a

‘lesser art’, the medium is enjoying a revival and is

justifiably being recognized as a valid fine art form.

Nartey’s process combines this traditional medium

with new technologies, by starting out with drawing

her subjects on an iPad, much like David Hockney

adopted in the early aughts. She always begins with

a line drawing of the subject’s face, which were

originally sourced from stock imagery and today are

generated from people she personally knows. Nartey

then adds the hairstyle, clothes, symbols, decorative

elements, and backgrounds that reveal a story. These

images are then printed on a large canvas which the

artist dubs her ‘underpainting’.

The canvas is then backed with three or four other

canvases and thicker materials to support the weight

of the stitching and fabric collage to follow. Nartey

then takes to the sewing machine, stitching

layers upon layers of embroidery thread over the

underpainting, at times deviating from the original

design. While her process is meticulous, she does

allow for intuition and improvisation to take place.

Nartey never really knows what type of stitching is

going to be applied until the moment she is working

on the piece. Just as an artist uses pencil or paint to

generate a line, add a highlight or deepen a shadow,

so does Nartey use thread. Its direction and weight

render the desired values, contrasts, and textures.

she states coyly. The artist estimates that each

tapestry has over two thousand yards of thread.