- X

- Tumblr

“Sinkhole” may seem a menacing title for a painting, unless that painting happens to be one in the “Kathleen Kucka: Slow Burn” exhibit at the Heather Gaudio Gallery in New Canaan.

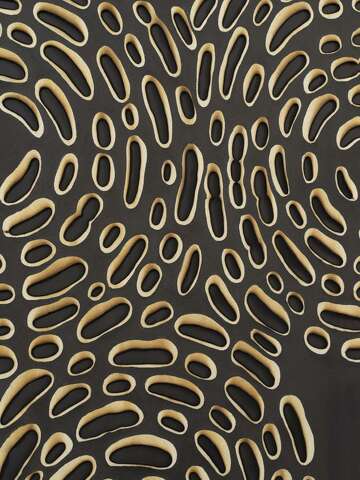

Kucka’s “Sinkhole” is really two paintings in one, with delightful depths. She made it by suspending one canvas over another, and using an electric charcoal lighter to burn holes in the upper canvas to reveal the canvas underneath. Altogether it has about 250 burn holes, arranged in rows, all slanting in the same direction and all the same jelly-bean shape.

Gallery director Rachael Palacios calls them ovoids and tries to describe how they interact with the underlying canvas. “Shadow is playing a part,” she says. “You have these ovoids repeating themselves and the way the light is playing on them, they almost double. They’re almost like Venn diagrams.”

“When I saw it in the gallery, I was really pleased with how activated those voids became with the light shining through. To me, it really popped,” she says. “The beautiful lighting creates shadows on the back canvas and as you move they change.”

In fact, “Sinkhole” is so kinetic it changes with the viewer’s slightest movement. Shapeshifting shadows come and go in those 250 ovoids. All are outlined with black burn marks and what look like faint halos of flame. Taller flames crown the ovoids in the very top row with pixie caps.

All but one of the paintings in the exhibit were made with the same scorching method, though the shadow play and depth varies. Most are patterns, some swirling, some linear, made from hundreds of small burn marks. The light brown of a perfectly toasted marshmallow is a prevalent hue.

A few seem to coalesce into images, like the almost butterfly in “Getting Ready to Believe.” Palacios says it’s “cheekier” than other paintings, pointing to fake ovoids that have been painted, not burned. Another titled “Sun Still Tender” consists of nine panels in which the beige upper canvas peels away from the blue lower one. Its shapes are bigger and pendulous, like panting tongues or drooping leaves, etched with arcing burn marks.

The newest pieces in the exhibit belong to a “Heartwood’ series of woodblock prints identified by color. Each is itself composed of four smaller prints of identical size. In one, “Heartwood White,” the burn marks are apparent and some function like stitches, binding the smaller prints to each other. But in “Heartwood Purple,” each component print bears a white starburst that can’t have been burned, except it was. Kucka says that white is what registers if the burn mark is made before inking. After any print comes off the press, she may make a second set of burn marks, leaving tears in the paper.

For the series, Kucka collaborated with a Brooklyn printmaker, Janis Stemmermann. Kucka herself divides her time between Manhattan and Falls Village. Her move here about five years ago, to a converted barn on a property once owned by the muralist Ezra Winter, inspired the Heartwood series.

“Being up here in Connecticut made me feel connected to the trees,” she says. “I wanted to bring that into my work. Then I realized using plywood as the skin of a tree would make a perfect material to print off.”

The move also freed her from certain city-imposed constraints. In the past she’s used all sorts of burning instruments, like hot plates and flat irons, that tended to produce smoke and the risk of fire.

Kucka herself, speaking from her studio in Falls Village, says she knew that by putting airspace between the two canvases there would be an interplay of light and shadow. She also intended an illusion of depth, so that “the painting went all the way back to the wall.” But she didn’t anticipate the full effect.